Hint... It is not what you think.

Here is a story you might find a bit laughable. At the end of the dark ages in what is now Italy, when knowledge was being reborn, anatomists would read from an ancient Greek text while their assistants dissected a human body and pointed out its parts. If the body looked different from what was written in the thousand year old text it was seen to be mutant, deviant, wrong. No matter that the ancient Greek knowledge was flawed and many of the rather ordinary observations that were being made would have improved dramatically upon what was known. Man, those early anatomists were dopes. It would take a major scientific revolution for anatomists to begin to actually observe and learn from dissections. The idea that more knowledge could be gained was a breakthrough. Isn't it crazy how hard it was for early scientists to figure out obvious things? Boy oh boy.

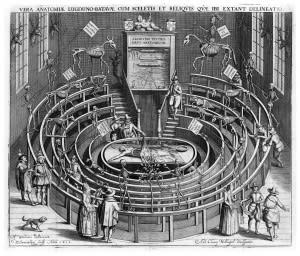

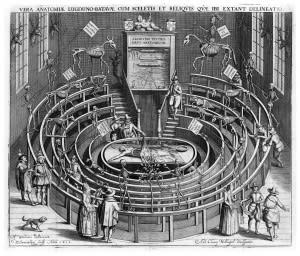

An early anatomy theater at the University of Leiden.

I was thinking about this the other day when I walked past a classroom

in which undergraduates were dissecting cats. Around the world,

millions of cats, dogs, pigs and other mammals, including thousands and

thousands of humans are dissected in anatomy classes. They are dissected

in order to teach students--including all of those who will eventually

operate on your body--about how an average mammal, amphibian or other

body works.

One can discuss the merits of having students perform dissections. One

can also discuss the morality of such dissections. I won't do either. I

want to get at something else, the issue of whether these students are

doing exactly the same sort of science that was being done at the end of

the dark ages.

In an average anatomy class dead animals are handed out to students. A tired/sometimes grumpy/overworked/underpaid teaching assistant

discusses how the dissection should be done. Students perform various

forms of butchery. Students label/point to/remove parts of the body on

which the teaching assistant has told them to focus. In focusing on

these parts of the body, the students are told about how it works, or at

least how it works in general. More body parts are dissected. More

knowledge is provided. The bodies are then thrown away in special

trashcans. The teaching assistant goes home to work on their thesis and

to wonder if he/she will ever get the job. The students go home to think

about other students/beer/ or other students. The whole process repeats

with a new group the next morning.

I don't mean to make fun of the hard work of students or teaching assistants.

What I do mean to make fun of is that we seem to now teach anatomy in

exactly the same way that it was being taught at the end of the dark

ages. Specifically, students look at bodies of animals, but are not

encouraged in any way to make real observations. Instead, they are

encouraged to look for what is already known and then if it does not

look quite right, do depict it the way it "should," look. Even where the

differences among bodies are noted, they are seldom measured. Even when

measurements are taken, they are seldom recorded.

Now, you might say, Rob, you are confusing things. At the end of the

dark ages we were ignorant about the body. Simple measurements could

produce new knowledge. Now we understand the body. Of course, there is

that difference. You are right, or you would be except that we still

don't understand the bodies of animals all that well. The function of

the appendix is under new scrutiny. The stomach too. In fact, when it

comes to basic morphology, the sorts of things that can be measured by

preoccupied students in large classes, we haven't made that much

progress in the last hundred years (This is where you, as the reader,

cue in on your favorite exception to my sweeping generalization and then

go on to mention it in the comments section). How and why do intestines

vary among individuals? How frequent are different deformations of

particular organs. Are there tradeoffs between investment in one organ

and in another? How frequent are rare mutations in the bodies of cats,

pigs or even humans, mutations that we still don't understand very well

at all. Such mutations are hard to study because of their very rarity,

but we dissect so many pigs, cats and other animals that even something

that turns up in just one in a million animals turns up somewhere in

some class each year. What else could be studied? I'm sure you can think

of obvious features I am missing. The point is there are discoveries

right beneath students as they look up at their teaching assistants or

teachers, but we are training them to ignore them, to see the general

story at the expense of the truth.

What now? I have one idea, probably an overly simple one, inspired by

work in citizen science. I would have students take real measurements

along with high-resolution digital images of the animals, including

humans, that they dissect. They would also take a sample of some tissue

of each animal (This might need to occur before the animals were

preserved which would be harder, but still possible). The images and

measurements would be sent to a database where they could be compared

with others of the same. The tissue would be shipped to a tissue bank.

With the database, anyone could compare the features of animals to

understand how much they vary. With the tissue bank, the genes

associated with unusual features could be narrowed down upon. With every

moment in class, the students, however sleepy, however focused on the

girl or boy in front of them, would be reminded that the body they are

looking at is, like their own body, still imperfectly, understood. That

was the revelation that would come after the dark ages, in the late

renascence. It is a revelation we would do well to build upon as we

consider how our own science and education might, together, be reborn,

or, if not reborn, just done in such a way as to allow students to pay a

little more attention to the dead pig in the hand, which, as they say,

is worth ten in the book. Maybe they don't really say that, but you get

the idea.

An early anatomy theater at the University of Leiden.

I was thinking about this the other day when I walked past a classroom

in which undergraduates were dissecting cats. Around the world,

millions of cats, dogs, pigs and other mammals, including thousands and

thousands of humans are dissected in anatomy classes. They are dissected

in order to teach students--including all of those who will eventually

operate on your body--about how an average mammal, amphibian or other

body works.

One can discuss the merits of having students perform dissections. One

can also discuss the morality of such dissections. I won't do either. I

want to get at something else, the issue of whether these students are

doing exactly the same sort of science that was being done at the end of

the dark ages.

In an average anatomy class dead animals are handed out to students. A tired/sometimes grumpy/overworked/underpaid teaching assistant

discusses how the dissection should be done. Students perform various

forms of butchery. Students label/point to/remove parts of the body on

which the teaching assistant has told them to focus. In focusing on

these parts of the body, the students are told about how it works, or at

least how it works in general. More body parts are dissected. More

knowledge is provided. The bodies are then thrown away in special

trashcans. The teaching assistant goes home to work on their thesis and

to wonder if he/she will ever get the job. The students go home to think

about other students/beer/ or other students. The whole process repeats

with a new group the next morning.

I don't mean to make fun of the hard work of students or teaching assistants.

What I do mean to make fun of is that we seem to now teach anatomy in

exactly the same way that it was being taught at the end of the dark

ages. Specifically, students look at bodies of animals, but are not

encouraged in any way to make real observations. Instead, they are

encouraged to look for what is already known and then if it does not

look quite right, do depict it the way it "should," look. Even where the

differences among bodies are noted, they are seldom measured. Even when

measurements are taken, they are seldom recorded.

Now, you might say, Rob, you are confusing things. At the end of the

dark ages we were ignorant about the body. Simple measurements could

produce new knowledge. Now we understand the body. Of course, there is

that difference. You are right, or you would be except that we still

don't understand the bodies of animals all that well. The function of

the appendix is under new scrutiny. The stomach too. In fact, when it

comes to basic morphology, the sorts of things that can be measured by

preoccupied students in large classes, we haven't made that much

progress in the last hundred years (This is where you, as the reader,

cue in on your favorite exception to my sweeping generalization and then

go on to mention it in the comments section). How and why do intestines

vary among individuals? How frequent are different deformations of

particular organs. Are there tradeoffs between investment in one organ

and in another? How frequent are rare mutations in the bodies of cats,

pigs or even humans, mutations that we still don't understand very well

at all. Such mutations are hard to study because of their very rarity,

but we dissect so many pigs, cats and other animals that even something

that turns up in just one in a million animals turns up somewhere in

some class each year. What else could be studied? I'm sure you can think

of obvious features I am missing. The point is there are discoveries

right beneath students as they look up at their teaching assistants or

teachers, but we are training them to ignore them, to see the general

story at the expense of the truth.

What now? I have one idea, probably an overly simple one, inspired by

work in citizen science. I would have students take real measurements

along with high-resolution digital images of the animals, including

humans, that they dissect. They would also take a sample of some tissue

of each animal (This might need to occur before the animals were

preserved which would be harder, but still possible). The images and

measurements would be sent to a database where they could be compared

with others of the same. The tissue would be shipped to a tissue bank.

With the database, anyone could compare the features of animals to

understand how much they vary. With the tissue bank, the genes

associated with unusual features could be narrowed down upon. With every

moment in class, the students, however sleepy, however focused on the

girl or boy in front of them, would be reminded that the body they are

looking at is, like their own body, still imperfectly, understood. That

was the revelation that would come after the dark ages, in the late

renascence. It is a revelation we would do well to build upon as we

consider how our own science and education might, together, be reborn,

or, if not reborn, just done in such a way as to allow students to pay a

little more attention to the dead pig in the hand, which, as they say,

is worth ten in the book. Maybe they don't really say that, but you get

the idea.

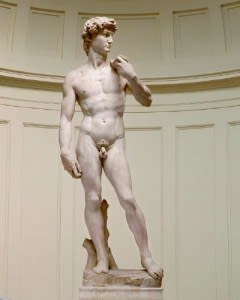

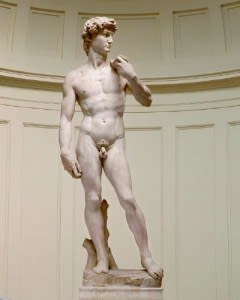

Evidence of Michelangelo's hard work paying attention during the dissections he performed.

I was going to end there but then I remembered the one place, the only

place in which students are actually taught to pay attention to the

bodies they see before them, art classes. In figure drawings classes a

naked man or woman stands in front of a room of students and is

observed, drawn, piece by piece. We could learn something from these art

students and their teachers. Ironically, the same was also true at the

end of the dark ages, when, long before the scientists began to pay

attention to bodies, the artists did. The artists had to, they were

charged by their instructors with portraying truths in contrast to the

science students who were (and are) charged only with portraying what is

already known.

Note: I use the term "dark ages" here. As one commenter notes, Early

Middle Ages is the term historians now tend to use. However, from the

point of view of biology in general and anatomy in particular, the times

were dark. For many fields of biology more was known in 100 BC than was

known in 1400 AD. Whatever you call the intervening years,

scientifically they were illuminated by precious little light.

Evidence of Michelangelo's hard work paying attention during the dissections he performed.

I was going to end there but then I remembered the one place, the only

place in which students are actually taught to pay attention to the

bodies they see before them, art classes. In figure drawings classes a

naked man or woman stands in front of a room of students and is

observed, drawn, piece by piece. We could learn something from these art

students and their teachers. Ironically, the same was also true at the

end of the dark ages, when, long before the scientists began to pay

attention to bodies, the artists did. The artists had to, they were

charged by their instructors with portraying truths in contrast to the

science students who were (and are) charged only with portraying what is

already known.

Note: I use the term "dark ages" here. As one commenter notes, Early

Middle Ages is the term historians now tend to use. However, from the

point of view of biology in general and anatomy in particular, the times

were dark. For many fields of biology more was known in 100 BC than was

known in 1400 AD. Whatever you call the intervening years,

scientifically they were illuminated by precious little light.

Courtesy: ScientificAmerican.com

Here is a story you might find a bit laughable. At the end of the dark ages in what is now Italy, when knowledge was being reborn, anatomists would read from an ancient Greek text while their assistants dissected a human body and pointed out its parts. If the body looked different from what was written in the thousand year old text it was seen to be mutant, deviant, wrong. No matter that the ancient Greek knowledge was flawed and many of the rather ordinary observations that were being made would have improved dramatically upon what was known. Man, those early anatomists were dopes. It would take a major scientific revolution for anatomists to begin to actually observe and learn from dissections. The idea that more knowledge could be gained was a breakthrough. Isn't it crazy how hard it was for early scientists to figure out obvious things? Boy oh boy.

An early anatomy theater at the University of Leiden.

I was thinking about this the other day when I walked past a classroom

in which undergraduates were dissecting cats. Around the world,

millions of cats, dogs, pigs and other mammals, including thousands and

thousands of humans are dissected in anatomy classes. They are dissected

in order to teach students--including all of those who will eventually

operate on your body--about how an average mammal, amphibian or other

body works.

One can discuss the merits of having students perform dissections. One

can also discuss the morality of such dissections. I won't do either. I

want to get at something else, the issue of whether these students are

doing exactly the same sort of science that was being done at the end of

the dark ages.

In an average anatomy class dead animals are handed out to students. A tired/sometimes grumpy/overworked/underpaid teaching assistant

discusses how the dissection should be done. Students perform various

forms of butchery. Students label/point to/remove parts of the body on

which the teaching assistant has told them to focus. In focusing on

these parts of the body, the students are told about how it works, or at

least how it works in general. More body parts are dissected. More

knowledge is provided. The bodies are then thrown away in special

trashcans. The teaching assistant goes home to work on their thesis and

to wonder if he/she will ever get the job. The students go home to think

about other students/beer/ or other students. The whole process repeats

with a new group the next morning.

I don't mean to make fun of the hard work of students or teaching assistants.

What I do mean to make fun of is that we seem to now teach anatomy in

exactly the same way that it was being taught at the end of the dark

ages. Specifically, students look at bodies of animals, but are not

encouraged in any way to make real observations. Instead, they are

encouraged to look for what is already known and then if it does not

look quite right, do depict it the way it "should," look. Even where the

differences among bodies are noted, they are seldom measured. Even when

measurements are taken, they are seldom recorded.

Now, you might say, Rob, you are confusing things. At the end of the

dark ages we were ignorant about the body. Simple measurements could

produce new knowledge. Now we understand the body. Of course, there is

that difference. You are right, or you would be except that we still

don't understand the bodies of animals all that well. The function of

the appendix is under new scrutiny. The stomach too. In fact, when it

comes to basic morphology, the sorts of things that can be measured by

preoccupied students in large classes, we haven't made that much

progress in the last hundred years (This is where you, as the reader,

cue in on your favorite exception to my sweeping generalization and then

go on to mention it in the comments section). How and why do intestines

vary among individuals? How frequent are different deformations of

particular organs. Are there tradeoffs between investment in one organ

and in another? How frequent are rare mutations in the bodies of cats,

pigs or even humans, mutations that we still don't understand very well

at all. Such mutations are hard to study because of their very rarity,

but we dissect so many pigs, cats and other animals that even something

that turns up in just one in a million animals turns up somewhere in

some class each year. What else could be studied? I'm sure you can think

of obvious features I am missing. The point is there are discoveries

right beneath students as they look up at their teaching assistants or

teachers, but we are training them to ignore them, to see the general

story at the expense of the truth.

What now? I have one idea, probably an overly simple one, inspired by

work in citizen science. I would have students take real measurements

along with high-resolution digital images of the animals, including

humans, that they dissect. They would also take a sample of some tissue

of each animal (This might need to occur before the animals were

preserved which would be harder, but still possible). The images and

measurements would be sent to a database where they could be compared

with others of the same. The tissue would be shipped to a tissue bank.

With the database, anyone could compare the features of animals to

understand how much they vary. With the tissue bank, the genes

associated with unusual features could be narrowed down upon. With every

moment in class, the students, however sleepy, however focused on the

girl or boy in front of them, would be reminded that the body they are

looking at is, like their own body, still imperfectly, understood. That

was the revelation that would come after the dark ages, in the late

renascence. It is a revelation we would do well to build upon as we

consider how our own science and education might, together, be reborn,

or, if not reborn, just done in such a way as to allow students to pay a

little more attention to the dead pig in the hand, which, as they say,

is worth ten in the book. Maybe they don't really say that, but you get

the idea.

An early anatomy theater at the University of Leiden.

I was thinking about this the other day when I walked past a classroom

in which undergraduates were dissecting cats. Around the world,

millions of cats, dogs, pigs and other mammals, including thousands and

thousands of humans are dissected in anatomy classes. They are dissected

in order to teach students--including all of those who will eventually

operate on your body--about how an average mammal, amphibian or other

body works.

One can discuss the merits of having students perform dissections. One

can also discuss the morality of such dissections. I won't do either. I

want to get at something else, the issue of whether these students are

doing exactly the same sort of science that was being done at the end of

the dark ages.

In an average anatomy class dead animals are handed out to students. A tired/sometimes grumpy/overworked/underpaid teaching assistant

discusses how the dissection should be done. Students perform various

forms of butchery. Students label/point to/remove parts of the body on

which the teaching assistant has told them to focus. In focusing on

these parts of the body, the students are told about how it works, or at

least how it works in general. More body parts are dissected. More

knowledge is provided. The bodies are then thrown away in special

trashcans. The teaching assistant goes home to work on their thesis and

to wonder if he/she will ever get the job. The students go home to think

about other students/beer/ or other students. The whole process repeats

with a new group the next morning.

I don't mean to make fun of the hard work of students or teaching assistants.

What I do mean to make fun of is that we seem to now teach anatomy in

exactly the same way that it was being taught at the end of the dark

ages. Specifically, students look at bodies of animals, but are not

encouraged in any way to make real observations. Instead, they are

encouraged to look for what is already known and then if it does not

look quite right, do depict it the way it "should," look. Even where the

differences among bodies are noted, they are seldom measured. Even when

measurements are taken, they are seldom recorded.

Now, you might say, Rob, you are confusing things. At the end of the

dark ages we were ignorant about the body. Simple measurements could

produce new knowledge. Now we understand the body. Of course, there is

that difference. You are right, or you would be except that we still

don't understand the bodies of animals all that well. The function of

the appendix is under new scrutiny. The stomach too. In fact, when it

comes to basic morphology, the sorts of things that can be measured by

preoccupied students in large classes, we haven't made that much

progress in the last hundred years (This is where you, as the reader,

cue in on your favorite exception to my sweeping generalization and then

go on to mention it in the comments section). How and why do intestines

vary among individuals? How frequent are different deformations of

particular organs. Are there tradeoffs between investment in one organ

and in another? How frequent are rare mutations in the bodies of cats,

pigs or even humans, mutations that we still don't understand very well

at all. Such mutations are hard to study because of their very rarity,

but we dissect so many pigs, cats and other animals that even something

that turns up in just one in a million animals turns up somewhere in

some class each year. What else could be studied? I'm sure you can think

of obvious features I am missing. The point is there are discoveries

right beneath students as they look up at their teaching assistants or

teachers, but we are training them to ignore them, to see the general

story at the expense of the truth.

What now? I have one idea, probably an overly simple one, inspired by

work in citizen science. I would have students take real measurements

along with high-resolution digital images of the animals, including

humans, that they dissect. They would also take a sample of some tissue

of each animal (This might need to occur before the animals were

preserved which would be harder, but still possible). The images and

measurements would be sent to a database where they could be compared

with others of the same. The tissue would be shipped to a tissue bank.

With the database, anyone could compare the features of animals to

understand how much they vary. With the tissue bank, the genes

associated with unusual features could be narrowed down upon. With every

moment in class, the students, however sleepy, however focused on the

girl or boy in front of them, would be reminded that the body they are

looking at is, like their own body, still imperfectly, understood. That

was the revelation that would come after the dark ages, in the late

renascence. It is a revelation we would do well to build upon as we

consider how our own science and education might, together, be reborn,

or, if not reborn, just done in such a way as to allow students to pay a

little more attention to the dead pig in the hand, which, as they say,

is worth ten in the book. Maybe they don't really say that, but you get

the idea.  Evidence of Michelangelo's hard work paying attention during the dissections he performed.

I was going to end there but then I remembered the one place, the only

place in which students are actually taught to pay attention to the

bodies they see before them, art classes. In figure drawings classes a

naked man or woman stands in front of a room of students and is

observed, drawn, piece by piece. We could learn something from these art

students and their teachers. Ironically, the same was also true at the

end of the dark ages, when, long before the scientists began to pay

attention to bodies, the artists did. The artists had to, they were

charged by their instructors with portraying truths in contrast to the

science students who were (and are) charged only with portraying what is

already known.

Note: I use the term "dark ages" here. As one commenter notes, Early

Middle Ages is the term historians now tend to use. However, from the

point of view of biology in general and anatomy in particular, the times

were dark. For many fields of biology more was known in 100 BC than was

known in 1400 AD. Whatever you call the intervening years,

scientifically they were illuminated by precious little light.

Evidence of Michelangelo's hard work paying attention during the dissections he performed.

I was going to end there but then I remembered the one place, the only

place in which students are actually taught to pay attention to the

bodies they see before them, art classes. In figure drawings classes a

naked man or woman stands in front of a room of students and is

observed, drawn, piece by piece. We could learn something from these art

students and their teachers. Ironically, the same was also true at the

end of the dark ages, when, long before the scientists began to pay

attention to bodies, the artists did. The artists had to, they were

charged by their instructors with portraying truths in contrast to the

science students who were (and are) charged only with portraying what is

already known.

Note: I use the term "dark ages" here. As one commenter notes, Early

Middle Ages is the term historians now tend to use. However, from the

point of view of biology in general and anatomy in particular, the times

were dark. For many fields of biology more was known in 100 BC than was

known in 1400 AD. Whatever you call the intervening years,

scientifically they were illuminated by precious little light.Courtesy: ScientificAmerican.com

No comments:

Post a Comment